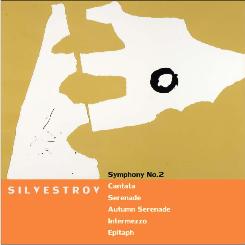

Valentin Silvestrov - Symphony No. 2 etc (2000)

Valentin Silvestrov - Symphony No. 2 etc (2000)

1. Symphony No. 2 (1965) for flute, timpani, piano and string orchestra Igor Blazhkov, conductor (Leningrad, 1967) 2. Cantata (1973) for soprano and orchestra on the words by Tyutchev and Blok Nelly Lee, soprano; Igor Blazhkov, conductor (Kiev, 1980) 3. Serenade (1978) for strings Alexander Rudin, conductor (Moscow, 1993) 4. Autumn Serenade (1980... 2000) for chamber orchestra Ludmila Voinarovskaya, soprano; Virko Baley, conductor (Kiev, 2000) 5. Intermezzo (1983, rev. 1993) for chamber orchestra Virko Baley, conductor (Kiev, 1994) 6. Epitaph (1999) for piano and string orchestra Virko Baley, conductor (Kiev, 2000)

"Music is still song, even if one cannot literally sing it: it is not a philosophy, not a world-view. It is, above all, a chant, a song the world sings about itself, it is the musical testimony to life." -- Valentin Silvestrov

It's not at all hard to hear the image of a "world singing itself its own song" in Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov's works. His string quartets, his songs, and his masterful symphonies all radiate with the slow steady force of a rotating planet, spinning lonesomely in the void. The notion that these vast, lethargic bodies sing to themselves as they turn, and we hear their music as a symphony or song cycle, admittedly carries an aspect of Romantic fancy to it. But the image also voices a serious metaphor for Silvestrov -- the concept of "meta-music," a music which hovers around, above, and especially after all other musics, like an atmosphere encircling a post-apocalyptic globe. Silvestrov has written much about the idea of "coda" and "epilogue" in his music, that place in which there is "a gathering of resonances, a form which is open." This coda-state is for Silvestrov "not the end of music as an art, but the end of music, an end in which it can linger for a very long time. It is very much in the area of the coda that immense life is possible." Hence Silvestrov's "metaphorical style" from the 1970s onwards: a body of slow, lovely, and astoundingly detailed "postludes," emanating the air of a Mahler adagio through vast waves of time and subtle decay.

Valentin Vasil'yevich Silvestrov was born in Kiev, Ukraine, on September 30, 1937, arguably the darkest year in the Russian history. He came rather late to music, beginning study at 15, first privately and then at an evening music school. By 1955, he graduated with a gold medal and enrolled at the Kiev Institute of Construction Engineering; but three years later Silvestrov began serious pursuit of music at the Kiev Conservatory, studying with Lyatoshyns'ky and Revutsky. Even with earliest works like the Piano Quintet (1961), Silvestrov was already drawn to the dramatic potential in contrasting strong tonality with strong atonality; in his massive Third Symphony "Eskhatofoniya" (1966), this preoccupation with polarities took the form of "cultural" (strictly notated) sounds and "mysterious" (improvised) ones. The place of magic and invocation -- those elements that always defy material, that arise only in the process and afterwards -- began to rest more firmly in Silvestrov's works.

1971's gigantic Drama for piano trio -- "virtually a clinical study of an artistic crisis," Silvestrov's biographer writes -- was a breakthrough work. And it was beginning in 1973 that Silvestrov embarked on his "metaphorical" or "allegorical" style, strongly reminiscent of late-Romantic cliché, to which he still adheres today -- "metaphorical" because Silvestrov knows these sounds to be irrefutably "past" and has no interest in merely "resurrecting" them; and "allegorical," because Silvestrov wishes to use this music obliquely, as an estranged means rather than a predictable end.

Silvestrov's Symphony No. 5 of 1982 is perhaps an ideal symbol of this style: in its three-quarter-hour cycle of nine slow movements, it "recycles" a whole world of banal, almost kitschy melodies on its scarred, cloudy surface. But underneath this floating music lies a tremendous complexity, both technically and emotionally; the accumulative expressive effect is undeniable and unexpected. Malcolm MacDonald perhaps put it best when he wrote that the "Russian sense of lamentation...reaches in Silvestrov a new expressive stage: he seems to compose, not the lament itself, but the lingering memory of it, the mood of sadness that it leaves behind." --- Seth Brodsky, allmusic.com

download: uploaded yandex 4shared mediafire solidfiles mega zalivalka filecloudio anonfiles oboom

Last Updated (Saturday, 10 May 2014 14:23)